Online Harms: The Way Forward

- by William Perrin, Trustee, Carnegie UK Trust, Maeve Walsh, Carnegie Associate and Professor Lorna Woods, University of Essex

- 14 December 2020

- 12 minute read

Publication of the UK Government’s final policy is imminent and will hit their promised “end of the year” deadline. We hope that the much-delayed Bill will follow “early in the new year”, as has been promised. What are the issues to look out for?

The policy vacuum since the Government’s last publication (the interim response on the White Paper, last February) has led to intense speculation: what companies and harms will be within scope for the legislation; the balancing act between the right to freedom of speech and the right to user safety; how the regime sits with wider media freedoms; and the nature of its enforcement and sanctions. Civil society campaigns have intensified and cross-party coalitions have solidified. Tech company lobbying and PR operations have apparently ratcheted up in response.

What we do know is that – from leading the world in this area a couple of years ago – the UK’s proposals will now be jostling for position in the middle of an international pack. The Government of Ireland published the General Scheme of the Online Safety and Media Regulation Bill on 9th December; the European Digital Services Act is due to be published on 15th December; proposals from Canada are expected in January and details of President-Elect Biden’s ‘National Taskforce on Online Harassment and Abuse’ are awaited with great interest. The UK might still be the first to get modern powers in place, but has a race on its hands.

Our work at Carnegie helped to unlock regulatory solutions to a problem that had been seen as too big and too complex to solve. In 2018, Professor Lorna Woods and William Perrin began to describe the challenges around online harms as being of system regulation, rather than direct content regulation. Hitherto discussion had largely been about takedown, publisher liability and criminal law. In highly influential work at Carnegie, Woods and Perrin changed the focus by suggesting that the systems run by platforms can be harmful. That unlocked a range of regulatory tools used in other sectors to manage harmful systems. In the UK context, Woods and Perrin put forward a statutory duty of care, enforced by a regulator within a regime of balanced rights, a model the UK Government has taken up. As regimes begin to emerge in other jurisdictions, we can see that the structures Woods and Perrin first set out – regulating systems, leading to risk assessment and mitigation, civil regulation and balancing rights – are being adopted.

We hope that our talks with international policymakers in the UN, the European Commission, the Council of Europe and within the Irish, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand governments will lead to the Carnegie approach continuing to be taken up widely.

We are ready to work with the UK Government and Parliamentarians of all parties to help ensure that the UK delivers the world-leading regulation it has promised for so long. In the meantime, here’s what we think it should look like to reach that bar.

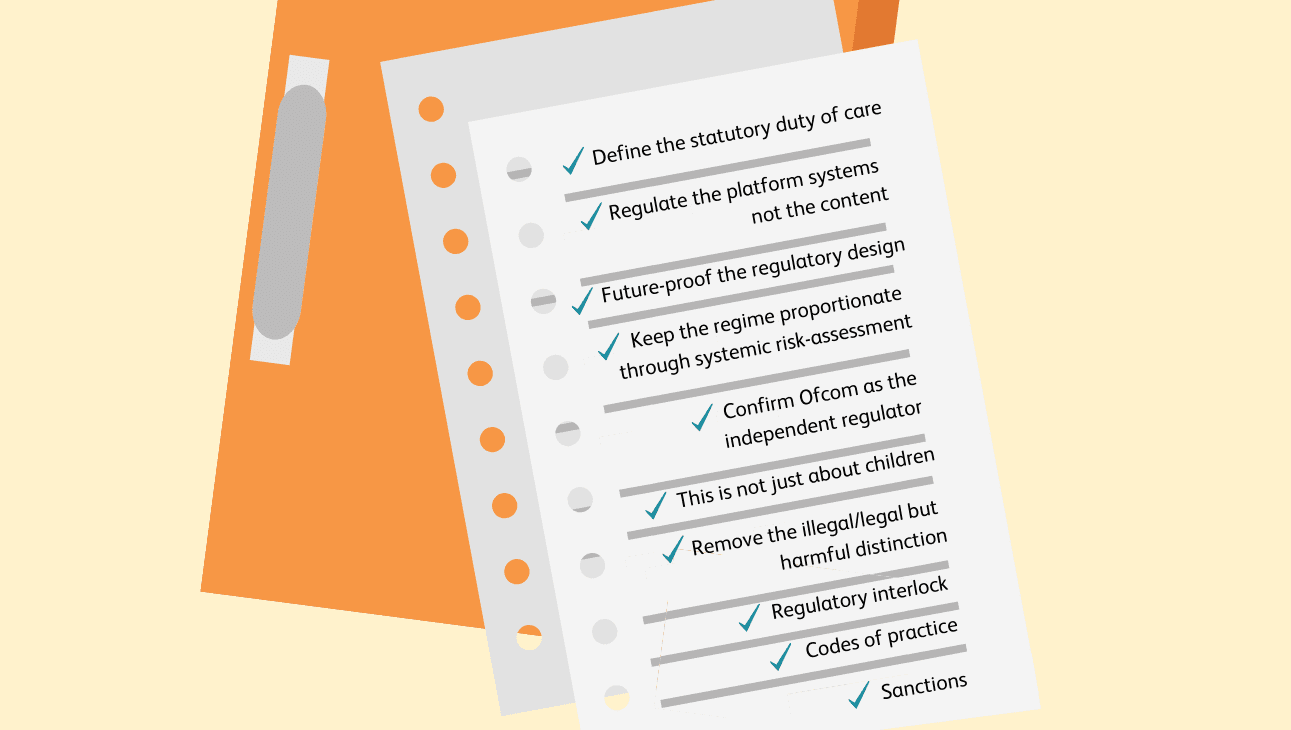

Define the statutory duty of care

The government should now set out its first draft of a statutory duty of care. The Carnegie risk-based approach uses the vehicle of a statutory duty of care set out in law by Parliament (not by the courts – the ‘tortious’ duty of care familiar across the common law world is a distant cousin). A ‘statutory duty of care’ as normally defined requires companies to take reasonable steps to prevent foreseeable harms. It has been used successfully for over 40 years to regulate the complex and varied domain of health and safety at work in the UK and the approach in general is well understood. We have set out in our draft Bill how this approach can be applied to online harms by amending the Communications Act 2003. This is a simple, but effective, approach.

Regulate the platform systems not the content

Every single pixel a user sees on a social media service is there because of decisions taken by the company that run the service or the platform: the design, the systems and the resources put into operating it. A regulatory regime that bites at the platform level, not at the level of individual pieces of content, puts the responsibility on the platform to ensure the risk of foreseeable harm is reduced for all users, which is how regulation works in other, equally complex, sectors.

It is the design of the service that creates the vectors through which multiple harms occur; each design choice has an impact across a range of harms. If the UK Government focuses its regulation on the platforms’ systems and design, it can stave off potentially time-consuming and arcane debates in Parliament around every item in an unwieldy “shopping list” of harms – and indeed avoid the much-feared, but seasonally appropriate, “Christmas Tree” Bill which might collapse under the weight of the concessionary baubles.

Future-proof the regulatory design

Related to this, we believe that a harm-based, outcome-orientated regulatory framework is flexible and future-proof in an area where technological change and the development and deployment of new services is particularly rapid. It allows decisions to be delegated to the independent regulator, based on an evidence-based approach, and so ensures that the regulatory regime is not out of date as soon as it is introduced. This draws on the well-established “precautionary principle”, on which we wrote at length in our 2019 reference paper.

This also best fits with a framework based on rights: it balances rights to physical and mental integrity with rights to freedom of speech and keeps Parliament and, crucially, the Government, at a distance from matters pertaining to speech. Professor Woods’ comprehensive paper on this subject explains this further.

Keep the regime proportionate through systemic risk-assessment

Companies who operate services covered by the duty of care should undertake rigorous risk assessments of all aspects of the service, which are kept continuously up to date. That requirement applies to the biggest social media companies in the world as well as the smallest start-up, where building “safety by design” in from the outset should become the norm. Everything hinges on competent assessment of risk and reaction to it. A risk-based approach is familiar in many jurisdictions for regulating corporate behaviours in the public interest. The risk management regime should be systemic – affecting the underlying design and operation of systems. Systems break down into roughly the following aspects: the underlying system design, terms of service at enrolment, the software used to distribute material, other software used to influence user behaviour, user self-management tools (how users can filter material for themselves), complaints systems and resolution of complaints systems. Again, these aspects apply to all social media companies and services, regardless of size.

Confirm Ofcom as the independent regulator

We assume that this is what the UK Government will do; its interim response in February said it was “minded” to do so. Ofcom has a proven track record of dealing with some of the world’s largest companies, using evidence-based regulation and litigation, and has successfully delivered balanced judgements on broadcasting issues that are not dissimilar to social media harms for many years. It is independent and arms-length from government and its Board is not made up of political appointees. It has successfully grown in the past when new responsibilities have been handed to it and can start work on implementing this regime immediately. Indeed Ofcom has recently taken on responsibility for implementing the regulation of video-sharing platforms, so its appointment in relation to wider Online Harms makes even more sense. If the Government decides to set up a new regulator it will be delaying any meaningful action on online harms for a least another 3-4 years at significant extra cost.

This is not just about children

There is no doubt that regulation of online harms is long overdue for children, particularly those who are at risk of the most horrific sexual abuse and exploitation online, including radicalisation as well as grooming by sexual predators. We applaud the work of organisations such as the NSPCC and 5 Rights Foundation in campaigning for a statutory duty of care and a “safety by design” approach that will have ramifications for online safety way beyond the communities of interest they represent. But the UK Government cannot and should not limit the scope to child safety and expect others to be protected by greater media literacy and/or the better enforcement of terms and conditions.

Remove the illegal/legal but harmful distinction

This distinction has not served the UK Government’s handling of the online harms policy development process well and has opened up unnecessary and divisive arguments about rights to free speech and government censorship, without the requisite clarity from the Government on how its proposals would operate in practice. Moreover, as the Government sought to allay such fears, it has indicated a much-reduced scope of the Bill to cover. The recent suggestion that “legal but harmful” content, including misinformation and disinformation that could cause public health harms (eg fake Covid 19 health cures, conspiracy theories and anti-vaxx campaigns), would require companies only to enforce their own terms and conditions has drawn criticism.

A risk-based, systemic approach takes the responsibility away from the regulator in adjudicating on individual pieces of content and instead requires the platforms to demonstrate how they have reduced the reasonably foreseeable risk of harm occurring from the design of their services. In the case of mitigating the risk of “legal but harmful”, this comes down to the way in which the platforms facilitate and even encourage the sharing of extreme or sensationalist content designed to cause harm: eg the operation of their recommender algorithms and other means of promotion; processes to determine the identity of users, to address bot nets and fake accounts; the size of “closed” groups; micro-targeting of content; the impact of “frictionless” likes/share functions, etc.

All of these design decisions play a role in the spread of harmful content to the extent that it causes real-world harm to users or society; the regime should not just be about “take down” or content – there are many more options available in the regulatory toolkit. Including these aspects within the risk-assessment requirements for companies, with a view to reducing the risk of the following harms to users, is the most effective way to ensure the broadest possible scope for the Bill while allowing it to remain flexible for future harms to be added, should Ofcom assess that there is sufficient evidence:

- Fraud and scams: this is illegal, criminal behaviour but the UK Government, to date, has indicated that it is outwith the scope of the Online Harms Bill, despite calls from senior figures in the financial and consumer sectors for it to be included.

- Public health harms: as we argued in our April 2020 blog, had a statutory duty of care been in place prior to the pandemic, it would have caught much of the damaging misinformation and disinformation in the spring as well as making inroads into the influence of the online, organised anti-vaxx campaigns well before the Covid 19 vaccine deployment.

- Online abuse and intimidation as reported by, for instance, Glitch.

- Harms to democracy and the electoral process:

- Self-harm

- Bullying

- Body dysmorphia

Regulatory interlock

It may appear at first sight that including many of the above harms in scope might overburden Ofcom but, without including them, we believe there will be significant gaps in the effectiveness of the regime. We do not propose that Ofcom has to make itself an expert regulator in all these areas but that instead the system includes a mechanism for it to co-operate with and receive evidence from specialist, competent regulators in other sectors who can hand over evidence of the scale and nature of the harm they have identified occurring on online platforms, for Ofcom to address through its Online Harms powers. We have described this system here and would see it applying, for example, to the work of regulators in the electoral, financial, consumer, product safety and other sectors.

Codes of practice

The UK Government set out in the White Paper a number of indicative codes of practice to address different harms and promised the introduction of two to address illegal activity– terrorism and child sexual exploitation and abuse – drawn up by the Home Office for adoption (on a voluntary basis at first) by industry. We have been working with civil society partners to draft a third – on hate crime – that we believe is necessary and that should sit alongside the other two “illegal” harms. We will publish this in draft shortly. Beyond that, the regulation should empower the regulator to implement/fill in the framework Parliament set through codes of practice that it either: agrees with industry and civil society, adopts from codes industry/civil society proposes or imposes from the regulator itself (e.g., on terrorism). Codes should include in particular how to assess risks rather than focusing on content and speech.

Sanctions

It is still not clear (in a micro economic sense) what sanctions are effective on the biggest companies – fines up to a % of global turnover, etc. some sort of named director liability (as in financial services) might be an option. In the UK, people are floating an order to ISPs to block a range of DNS used by the platform at the border (as a proxy for not having the threat of taking away a licence).

Finally, we hope the government will provide some thoughts on its approach to legislation – will there be pre-legislative scrutiny, will they amend the Communications Act, as Carnegie proposed in our draft bill?

Help us make the case for wellbeing policy

Keep in touch with Carnegie UK’s research and activities. Learn more about ways to get involved with our work.

"*" indicates required fields